Taiwan invests in subsequent technology of expertise with slew of chip faculties

"By cultivating talent in semiconductors, we are racing against time," Tsai said in December at the opening of National Tsing Hua University's Semiconductor Res

- by B2B Desk 2022-03-11 09:06:23

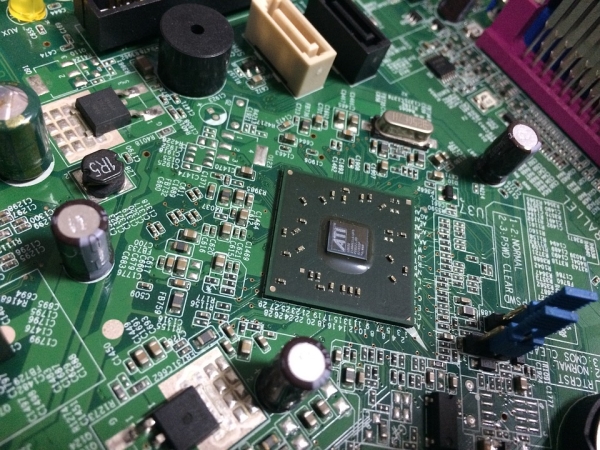

Taiwan is racing to host specialized year-round "chip schools" to train semiconductor engineers in its latest technology and cement its dominance of the core {industry}. The plans, championed by President Tsai Ing-wen, come as chip companies pour billions of dollars into ever-increasing capabilities to create the "brains" that power everything from smartphones to fighter jets amid shortage around the world.

TSMC's big chip alone this year will spend $44 billion and hire more than 8,000 workers. Jack Sun, who retired as TSMC's chief expertise officer in 2018 and became dean of one of several new semiconductor graduate colleges last year, warned Reuters that chip companies want more and more experience to compete on the worldwide stage.

"I've actually spent some of my golden years developing talent," Sun recalled amusedly, before stating that his former TSMC teammate Berne Lane is older and the dean of another chip school. Sun Wulin, {industry} turned educator, exemplifies the federal government's approach to strengthening ties between industry and academia to remain an important node within the international chip supply chain.

"By cultivating talent in semiconductors, we are racing against time," Tsai said in December at the opening of National Tsing Hua University's Semiconductor Research School. Taiwan authorities have teamed up with major chip companies to pay for these universities.

The Ministry of Education reported that the first four were created in secondary universities in the last year, each with a quota of about 100 undergraduate and doctoral students, and one more was accepted. Tsai mentioned it in another presentation.

The shortage of chip expertise is a major concern for the democratically elected authorities, whose "industry" is critical to the financial progress and security of the entire country, particularly as China ramps up military fatigue to reclaim its sovereignty over Taiwan.

‘TOP PRIORITY’

Even before chips were in short supply around the world, companies worried that a crisis of expertise could hinder a thriving {industry}, said Terry Tsao, president of SEMI Taiwan {Industry} Group. In September 2019, Tsao and about 20 Taiwanese and overseas chip executives met with Tsai and urged the federal government to address the issue.

"Everyone thinks this is the top priority," Tsao said. Now, while international sites promise billions to buy domestic chips manufacturing and companies are scrambling to build new plants, the need to design, manufacture, and test chips has intensified. In the last quarter of 2021, there were roughly 34,000 {industry} jobs per month on 104 Job Bank, a beloved Taiwanese recruitment platform, roughly 50 percent larger than a year ago, in line with the knowledge given by 104.

Despite high demand for employees, Taiwan, which has one of the lowest starting rates in the world, has been churning out fewer engineers over the past decade. Fewer still enroll in doctoral programs that bring together the best engineers to develop advanced applied sciences.

Competing for a restricted pool, Taiwanese companies have implemented higher salaries, greater distances between parents, advertisements and scholarships to steal engineers from various companies and hire contemporary experts from universities.

Taiwan now cannot satisfy the wishes of the domestic {industry}, and foreign competitors will have an additional impact on improving its R&D expertise in the long run, said chip designer MediaTek, which this year plans to employ more 2,000 R&D workers and double its diversity of Summer Interns to ensure prior experience.

Companies are also looking abroad: Taiwanese chipmaker United Microelectronics Corp., which plans to hire more than 1,500 new workers in Taiwan this year, told Reuters it is increasing its overseas recruiting channels.

‘NARROWING THE GAP’

Last May, Taiwan issued a regulation to facilitate cooperation between universities and companies in key areas of national interest, paving the way for chip universities.

More flexible guidelines allow these colleges to advertise company financing and improve college salaries. In addition to funding, the companies will help design curricula, send executives to give talks, provide consultants with chips to watch shows and advise on analytics initiatives.

With the rapid development of chip expertise, "there is a gap between what you study and what you need to use in the company," Su Yan-Kuin, dean of National Cheng Kung University's School of Chips, said in his place. work, while The employees assembled the door of the subsequent packages.

"We are working closely with industry, connecting industry and academia, thereby bridging the gap." Lin Chun Yu, 24, an upcoming Ph.D. student at Su College, will receive T$40,000 ($1,411) per month, the salary of undergraduate Ph.D. students.

In Taiwan sometimes you don't understand.

"The close cooperation with the industry now will be very beneficial for my studies and employment," he stated. While some in Taiwan are involved in a single semiconductor deal that will be priced across multiple industries, others say such prices are necessary.

"It will create imbalances in the ecosystem," Yeh-Win Quan, director of the Taiwan Semiconductor Research Institute, said of chip universities that attract college students from various fields.

"But there is no other choice now. Taiwan's lifeline, you must first hold on to it. If you don't hold on to it, how can you allow the Taiwanese economy to move forward?"

Also Read: Narayana Murthy’s Catamaran Ventures invests in gaming startup Loco

POPULAR POSTS

How a Free AI Visibility Tool Helps Businesses Grow in the AI Driven Search Era

by Aakash Ladha , 2026-03-06 10:40:04

Loan EMIs to Drop as RBI Slashes Repo Rate - Full MPC December 2025 Highlights

by Shan, 2025-12-05 11:49:44

Zoho Mail vs Gmail (2025): Which Email Platform Is Best for Businesses, Startups, and Students?

by Shan, 2025-10-09 12:17:26

PM Modi Launches GST Bachat Utsav: Lower Taxes, More Savings for Every Indian Household

by Shan, 2025-09-24 12:20:59

$100K H-1B Visa Fee Explained: Trump’s New Rule, Clarifications & Impact on Indian Tech Workers

by Shan, 2025-09-22 10:11:03

India-US Trade Deal Soon? Chief US Negotiator Arrives in Delhi as Talks Set to Begin Tomorrow

by Shan, 2025-09-15 11:54:28

Modi Meets Xi: Trump’s Tariffs, Strategic Autonomy, and the Future of Asia’s Power Balance

by Shan, 2025-09-03 06:40:06

RECENTLY PUBLISHED

Pine Labs IPO 2025: Listing Date, Grey Market Premium, and Expert Outlook

- by Shan, 2025-11-05 09:57:07

The Agentic Revolution: Why Salesforce Is Betting Its Future on AI Agents

- by Shan, 2025-11-05 10:29:23

Top 10 Insurance Companies in India 2026: Life, Health, and General Insurance Leaders Explained

- by Shan, 2025-10-30 10:06:42

OpenAI Offers ChatGPT Go Free in India: What’s Behind This Big AI Giveaway?

- by Shan, 2025-10-28 12:19:11

Best Silver Investment Platforms for 2025: From CFDs to Digital Vaults Explained

- by Shan, 2025-10-23 12:22:46

Subscribe now

Subscribe now