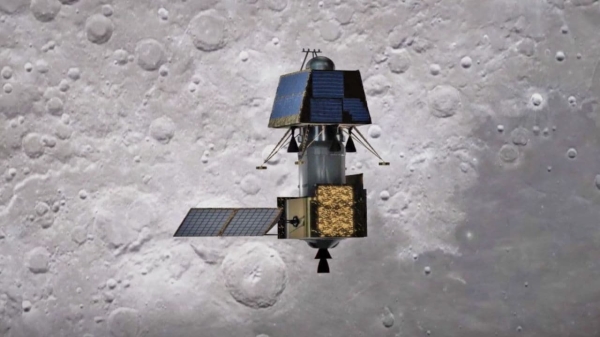

Chandrayaan - 3: Here's why ISRO's lunar ambitions are critical for Indian economy

After Chandrayaan-3 lands, the plan is to send a rover to the moon and explore the lunar south pole. But it's not just national pride on the line for this spac

- by B2B Desk 2023-08-23 10:08:31

More than just national pride will be on the line when India undertakes its second attempt to land on the moon later this week.

On August 23, the Indian Chandrayaan-3 will attempt to land on the moon, an event with the potential to unlock real economic benefits.

Chandrayaan-3 is the third lunar exploration mission by the Indian Space Research Organization, and if it’s successful, India will become the fourth country, after the United States, the former Soviet Union (now Russia), and China, to achieve a soft landing on the lunar surface.

A crash landing, like what happened with Chandrayaan-2, doesn't count.

After Chandrayaan-3 lands, the plan is to send a rover to the moon and explore the lunar south pole.

But it's not just national pride on the line for this spacefaring nation: Chandrayaan-3's success could have a very real impact on India's economy.

The world has already seen everyday benefits from previous space efforts, such as accessibility to clean drinking water with water recycling on the International Space Station, near-global Internet access provided by Starlink for education, and advances in solar power generation and health technologies.

With the increasing demand for global satellite imaging, positioning, and navigation data, multiple reports indicate that the world is already in a phase of explosive growth in the space economy.

Deloitte's report highlights how over USD 272 billion has been raised since 2013 through private equity in 1,791 companies.

In its annual report, the Space Corporation noted that the global space economy was already valued at USD 546 billion in the second quarter of 2023. This represents a 91 percent increase in value over the past decade.

For many countries, participating in the nascent space economy has the potential to have huge downstream enormous benefits for their economies, as well as inspiring their citizens to participate in the new space age.

India's space economy is expected to be worth USD 13 billion by 2025.

By comparison, Australia's Civic Space Strategy 2019-2028 aims to triple the sector's contribution to GDP to USD 12 billion and create an additional 20,000 jobs by 2030.

A successful moon landing will also reflect India's technological prowess.

Although NASA succeeded in getting humans to the moon during the Apollo Programme more than 50 years ago, many seem to have forgotten the incremental steps and huge sums of money it took to get there.

There were also many unknowns, including real worries that the lunar surface was so soft and dusty due to billions of years of meteorite bombardment, that spacecraft would sink to the surface like quicksand, a concern that proved unfounded.

But even with the advanced computing and cutting-edge technology of the 21st century, the challenges of spaceflight remain the same: Can your system maintain stable communications and operate autonomously under a wide range of extreme conditions?

India's first attempt to reach the moon using Chandrayaan-1 succeeded in nearly all of its mission goals and science objectives, including revealing evidence of water on the lunar surface for the first time.

But the Indian Space Research Organization lost contact with the spacecraft just 312 days after its intended two-year mission.

However, Chandrayaan-1 is considered by many to be a massive success, receiving awards from the National Space Society and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

On September 6, 2019, India once again attempted to reach the Moon using the Vikram lander carrying the Pragyan rover as part of the Chandrayaan-2 mission.

However, 2.1km above the lunar surface contact with the lander was lost, and images taken by NASA later confirmed that it had crashed into the surface.

Issues associated with the onboard coordination of the five engines and the lander's orientation during the camera coast phase and final braking phase of its descent were attributed to the failure of the spacecraft.

Issues with onboard software and autonomous landing sequences have also led to the failures of two other countries' lunar landing attempts in the past three years.

On 11 April 2019, the Israeli Beresheet lander attempted a soft landing on the northern section of the Mary Serenitatis, but the inertial measurement Unit gyroscope failed during the braking procedure, resulting in a loss of communications 2.1 km above the surface.

If it had been successful, Beresheet would have been the first successful privately funded mission and the first Israeli mission to the moon.

On April 25, 2023, privately funded Japanese company iSpace attempted a soft landing of their Hakuto-R lander carrying the United Arab Emirates Rashid rover.

Analysis by iSpace engineers later confirmed that the onboard computer was programmed to ignore the laser radar altimeter if it conflicted with the spacecraft's expected location.

Due to a last-minute change in the intended landing area, the sudden change in altitude as the spacecraft reached the top of the crater rim was interpreted as an error, causing the spacecraft to fly 5 km above Earth. The surface of the moon before running out of fuel collapses. to the surface.

Together, the failures of Chandrayaan-2, Beresheet, and Hakuto-R highlight the difficulties of modern spaceflight and the importance of software iteration, systems engineering, and change management, even in an age of advanced sensing and high processing power.

Taking the lessons learned from Chandrayaan-2, Chandrayaan-3 has several improvements from its predecessor.

The intended landing zone has been expanded to an area 4.2 km long and 2.5 km wide, which means that the spacecraft has a greater margin of error than the risk of picking a single point and drifting, as occurred with Chandrayaan-2.

Chandrayaan-3 will also have four engines with adjustable throttle and slew, as well as a laser Doppler accelerometer, meaning it can control its attitude and direction throughout the descent, unlike Chandrayaan-2.

The Vikram lander is carrying more sensitive versions of instruments already on the lunar surface, including a seismometer for detecting moonquakes, a Langmuir plasma probe to measure the behavior of charged particles from the sun on the lunar surface and a NASA-contributed retroreflector like the one left by Apollo 11.

A 10 cm thermal probe will also be inserted into the ground and provide measurements of the temperature gradient throughout the day, which could improve scientists' understanding of areas of stabilization of resources such as water ice at the Earth's poles.

The Vikram lander is also carrying a six-wheeled, 26-kilogram lunar rover called Pragyan, which is about the size of a golden retriever.

It carries two payloads: an alpha particle X-ray spectrometer and a laser-induced decay spectrometer to measure the composition of lunar rocks and soil.

Although these instruments have previously been used by NASA on several of its Mars rovers, as well as by the China National Space Administration on its Yutu rovers on the Moon, Pragyan will be exploring new areas.

If successful, Chandrayaan-3 will highlight how space has become more accessible and demonstrate India's continued tenacity and perseverance in achieving challenging missions.

It also bodes well for India's participation in the new space race to build permanent infrastructure on the moon. In 2021, China and Russia announced that they would build a lunar base together and invited others to join their international lunar research station, as an alternative to the American Artemis program. India became a signatory to the Artemis Accords in July 2023.

With each successful mission, humanity's knowledge of the lunar surface and environment continues to grow, which means fewer risks associated with reaching and staying on the moon.

Also Read: Paytm investing in AI to build Artificial General Intelligence software stack: CEO

POPULAR POSTS

How a Free AI Visibility Tool Helps Businesses Grow in the AI Driven Search Era

by Aakash Ladha , 2026-03-06 10:40:04

Loan EMIs to Drop as RBI Slashes Repo Rate - Full MPC December 2025 Highlights

by Shan, 2025-12-05 11:49:44

Zoho Mail vs Gmail (2025): Which Email Platform Is Best for Businesses, Startups, and Students?

by Shan, 2025-10-09 12:17:26

PM Modi Launches GST Bachat Utsav: Lower Taxes, More Savings for Every Indian Household

by Shan, 2025-09-24 12:20:59

$100K H-1B Visa Fee Explained: Trump’s New Rule, Clarifications & Impact on Indian Tech Workers

by Shan, 2025-09-22 10:11:03

India-US Trade Deal Soon? Chief US Negotiator Arrives in Delhi as Talks Set to Begin Tomorrow

by Shan, 2025-09-15 11:54:28

Modi Meets Xi: Trump’s Tariffs, Strategic Autonomy, and the Future of Asia’s Power Balance

by Shan, 2025-09-03 06:40:06

RECENTLY PUBLISHED

Pine Labs IPO 2025: Listing Date, Grey Market Premium, and Expert Outlook

- by Shan, 2025-11-05 09:57:07

The Agentic Revolution: Why Salesforce Is Betting Its Future on AI Agents

- by Shan, 2025-11-05 10:29:23

Top 10 Insurance Companies in India 2026: Life, Health, and General Insurance Leaders Explained

- by Shan, 2025-10-30 10:06:42

OpenAI Offers ChatGPT Go Free in India: What’s Behind This Big AI Giveaway?

- by Shan, 2025-10-28 12:19:11

Best Silver Investment Platforms for 2025: From CFDs to Digital Vaults Explained

- by Shan, 2025-10-23 12:22:46

Subscribe now

Subscribe now